Interesting Papers in Psychiatry - August 2025

Clozapine and Friends Edition

Keeping up with the latest papers in the dozen or so big psychiatry journals is pretty difficult for me, because I don’t always have a reason to go through them. So, what if I gave myself a reason by being a Very Original Substacker and trying to publish a piece every month two months quarter with the stuff I’ve come across that I think is interesting?

A disclaimer: I have not read through all of these things very carefully and so might have misinterpreted them. If you notice that I have, please let me know so I can correct myself!

Caring for Patients With Severe Anorexia Nervosa—A Capacity Evaluation Cannot Save Us

I’m always a fan of any piece that would like to remind us about the complexities of assessing capacity and this one does it particularly well for a particularly difficult topic.

This large (n = ~23,000) population based, retrospective study tried to answer the question: “Is there any evidence that augmenting clozapine with another antidopaminergic reduces psychiatric hospitalization?” Their results say that there is, but only for moderate doses of aripiprazole (9-16.4mg/day) when combined with high (≥330 mg/day) doses of clozapine.

They used a “within-individual design, using each individual as his/her own control to eliminate selection bias, and analyzed with stratified Cox models.” Apparently this solves a lot of the statistical problems with confounding by indication.

Predicting Diagnostic Progression to Schizophrenia or Bipolar Disorder via Machine Learning

Another attempt at trying to build models to predict the development of schizophrenia before it actually happens. I think it’s still an open question as to whether or not knowing this information would be useful in the first place; you’d think it might be, but the reality is that we can’t actually do all that much even if we know it’s coming.

This machine learning model performed OK, I guess? Sensitivity was 19.4%, which is actually pretty bad relative to non-ML based screens which range from 97-81% depending on your risk criteria. Specificity was quite high at 96.3%; non-ML models do somewhere between 67-59%. PPV was 10.8%, which means that the prevalence of schizophrenia in this sample was 2.26%, about double the rate in the normal population which makes sense given that the study population was drawn from a database of individuals with at least 2 contacts with the Danish mental health services.

You’d think that maybe this high specificity, low sensitivity tradeoff would be OK. After all, the social interventions that might be put into place are quite expensive. The problem is that schizophrenia — even in this enriched population — is so rare that a specificity of 96% isn’t enough. In a population of 10,000 individuals this model would catch only 44 true positives, but 365 false positives. That’s ~8 false positives for every true positive.

Safety and Efficacy of Repeated Low-Dose LSD for ADHD Treatment in Adults

Microdosing LSD over a 6 week period does not improve the symptoms of ADHD. Yadontsay.jpg As someone who has familiarity with both ADHD and LSD, I’m very confused as to why anyone would think that LSD would improve ADHD symptoms.

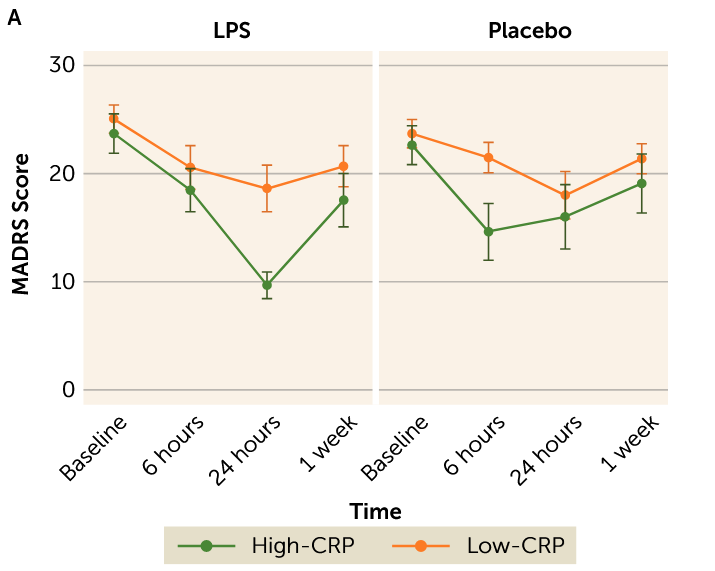

We’re back to doing the depression and inflammation thing again, I guess. This one is kinda interesting. They separated out people with an active diagnosis of MDD into groups with high blood CRP (a general inflammatory marker) and low CRP, gave them placebo or LPS (a molecule produced by bacteria that makes your immune system very upset), and looked to see how much worse their anhedonia (lack of interest/pleasure in things) got, among other things. Anhedonia got worse in both groups, but scores on the anhedonia scale used went up twice as much in the high CRP group compared to the low CRP group.

Maybe the most interesting thing about this study is that they also measured overall depressive symptoms with the MADRS and found a pretty enormous improvement in the high CRP group relative to the low CRP group 24h post-LPS.

This is pretty funny, but probably just due to small sample size and placebo effect?

I highlight this study not because I think the results are particularly interesting, but because I am totally confused as to what real-world conclusions anyone is supposed to draw from this study. “Telehealth service use” was defined as:

[When] respondents reported having spoken to a doctor, physician’s assistant, or nurse practitioner about their own health over phone, e-mail, or video call instead of going to an in-person appointment.

So… any patient who uses their patient portals to ask their doctor a question? Is this definition really going to draw lines between groups that will mean something?

FDA Eliminates the Clozapine REMS—What Comes Next?

Just an absolute banger of an article by Kelly, Kane, Love, and Cotes talking about the future of clozapine monitoring now that the FDA has (finally) done the sane thing and abolished the clozapine REMS. Let me play you the hits:

The mental health field should recognize that neutropenia is not the same as agranulocytosis or severe neutropenia… Having neutropenia does not coincide with agranulocytosis risk…

The peak incidence occurs at 30 to 54 days and is highest in the first 18 weeks. There are few cases beyond 6 months, and the risk declines to negligible levels after 1 to 2 years. Cases of agranulocytosis after 18 weeks occur at a rate of 0.39 per 1000 patient-years.

Furthermore, deaths from agranulocytosis are extremely rare… rates were less than 0.013% to 0.028% of cases treated.

Simvastatin as Add-On Treatment to Escitalopram in Patients With Major Depression and Obesity

Escitalopram + simvastatin didn’t reduce depressive symptoms at 12-weeks relative to escitalopram + placebo in patients with MDD and obesity. I mean… kinda one of those studies that makes you want to go “Did… did anyone really think that statins would improve depression?”

The most impressive thing about the study is that they had a 95.6% retention rate. Maybe we should be doing more clinical trials in Germany.

Esketamine Combined With SSRI or SNRI for Treatment-Resistant Depression

This was a retrospective cohort study of patients of 55,480 patients with treatment-resistant depression over 5-years. All were on esketamine, half with a concurrent SRI, other other half with a concurrent SNRI.

The SNRIs beat out SRIs pretty handily on the primary outcomes of all-cause mortality, hospitalization, and depressive relapse. This was not by small margins!

Patients in the esketamine + SNRI group had significantly lower all-cause mortality (5.3% vs 9.1%; P < .001), hospitalization rates (0.1% vs 0.2%; P < .001), and depression relapses (14.8% vs 21.2%; P < .001) compared to the esketamine + SSRI group

The SRI combo, however, showed a significant reduction in suicide attempts, but just barely:

The esketamine + SSRI group, [showed] a lower incidence of suicidal attempts (0.3% vs 0.5%; P = .04)

My first instinct is to say that there is some hidden variable that correlates strongly with likelihood of being on an SNRI, but I can’t think of anything all that obvious. There’s also no data in the paper about how long patients were maintained on esketamine treatment, which matters a great deal to me. If the average patient in this study is on esketamine for the majority of the 5-year study period, that says something quite different than those on it for 6-months.

Unless there are good RCTs out there looking at combination therapy, I think that this probably should push you to default to SNRIs in combo with esketamine.

We’ve known for a while that clozapine causes neutropenia, but does that translate into higher rates of infection? Hu et al. try to answer this question in 11,051 patients (1450 using clozapine and 9601 using olanzapine) schizophrenics who used either drug for at least 90-days.

The answer is “Probably, but only slightly.” Overall, patients on clozapine had an additional 1.26 infections per 100 person-years relative to patients on olanzapine. This means that if I treated 100 patients with clozapine, and 100 patients with olanzapine, I would see one additional infection in the clozapine group over the course of a year. As you might predict, the older the patient is, the bigger of an effect treatment seems to have. Patients over the age of 55 had an additional 4.7 infections per 100 person-years relative to olanzapine.

Most of this difference seems to be driven by an increased risk of respiratory and GI infections, which makes sense given that we already knew that antipsychotics increase the risk of both infective and aspiration pneumonia.

This is, perhaps, interesting to know, but doesn’t seem very likely to have any real world impact. Despite only being used in the sickest of the sick, clozapine probably reduces all-cause mortality in schizophrenics and might even beat out the other antidopaminergics.

I usually avoid bringing up pre-clinical papers for many reasons, but this one I think is worth at least throwing on your radar. The idea of trying to use the immune system to treat addiction is tantalizingly simple in theory; get the immune system to treat various drugs as persona non grata, bind them with antibodies and shuffle them out the door before they can act as intoxicants. In reality this is a vary complicated affair, as the researchers who tried to make a cocaine vaccine in mid-aughts will tell you. That one seems to have failed due to the relatively low response rates and the lack of efficacy after just a couple of months of treatment.

Unless you’ve been living under a rock, you are probably aware that there is a fentanyl epidemic in the United States, and right now our best treatment for opioid addiction is to basically just give patients different, longer acting opioids under a physician’s supervision. This approach works for some patients, but it’s no surprise that there are folks out there trying to figure out if there are better alternatives.

Enter Galbo-Thomma et al.. This group decided to just make a humanized monoclonal antibody (mAb) instead of trying to coax the immune system into making it via vaccine; this makes a lot of sense given that the cost of producing mAb’s has fallen by 3-10x since the mid 2000s.

A single injection of this mAb in rhesus monkeys modestly reduced self-administration for between 8-36 days; this result was dependent on how much fentanyl the monkeys were using at baseline. It also prevented fentanyl-induced respiratory depression for more than 2 weeks in some of the monkeys. Interestingly, this effect was not dose-dependent!

Symptom Provocation and Clinical Response to Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation

I’m mostly highlighting this paper because it introduced me to the concept of “symptom provocation” in TMS. Apparently “state-dependent effects of TMS have been demonstrated in the motor, visual, and memory systems where prestimulation neural activation increases susceptibility to TMS effects.” This is pretty cool!

Unfortunately, this meta analysis did not find any advantage for provocation vs. no provocation in treatment of OCD and nicotine dependence, though there is definitely a trend in the right direction. The authors point out that there are only 3 studies that did a head-to-head comparison of provocation vs. no provocation for nicotine dependence, and 2 of the 3 found provocation to be superior.

So, maybe leave some picture frames slightly askew, tell housekeeping to leave the bathroom just slightly dirty, and keep an opened pack of Marlboros in your desk… just in case.

> In a population of 10,000 individuals this model would catch only 44 true positives, but 365 false positives. That’s ~8 false positives for every true positive.

Thanks for bringing this part up. As someone who doesn't get into statistical weeds often enough, I forget about these things. I do wonder what the equivalent screening specificity for EASA programs is. I didn't read the study, but maybe the ML program is trying to identify clients before any symptoms and EASA screenings are higher specificity due to waiting for actual symptoms of psychosis. IDK.

I don't have access to the AN capacity assessment study, but that paper, and your comment on the complexities of capacity assessments, is intriguing to me. If you are ever feeling the itch to write a digestible synopsis on those complexities, know you will have at least one reader!

> My first instinct is to say that there is some hidden variable that correlates strongly with likelihood of being on an SNRI, but I can’t think of anything all that obvious

Could it just be that clinicians see SNRIs as second line therapies, so patients on them generally have more severe / treatment resistant depression, and ketamine has larger effect sizes in more severe depression / TRD?