Notes To My Residents: #1 - We Don't Collaborate With Delusions

Also some thoughts on the importance of believing in your own approach

A special thank you to Drs. Colon, Tiula, and MacDougald for their feedback on this piece.

I’ve been trying to find a format in which I can share my opinions without feeling the need to do extremely deep dives into the literature for every little thing. I finally came up with the idea of writing a series of essays about my decision making in psychiatry, geared towards explaining to my current and future residents what I’m thinking, why I think that way, and how I come to particular decisions.

I want to be clear that I do not think that the thought processes and conclusions I lay out in these essays represent some sort of objectively correct way of practicing psychiatry. Rather, they represent the best way I know how to practice psychiatry so far.

But enough preamble. Here’s the first installment of Notes To My Residents.

Fumbling Around

Learning how to deal properly with a delusional patient is a rather confusing experience. Your initial reaction (mine was) will probably be to offer your patient indisputable proof that they are wrong. This doesn’t really work.

I once had a psychotically depressed patient (let’s call her Kate) who swore to us every day for about a week that she knew her daughter was dead. How did she know this? Well, she just knew. We knew that Kate’s daughter was planning to visit her on Friday. We told Kate this, but Kate insisted that this was impossible — what part of “my daughter is dead” did we not understand, exactly? — and we would see how wrong we were when Friday came around and her daughter didn’t show up. So, Friday rolls around, Kate’s daughter (not dead) shows up, and we bring her to Kate’s room. Did this revelation bestow upon Kate some deep insight into the nature of her condition, shattering her delusional state? Of course not. She looked at her daughter in mild disbelief for half a minute, and then said “well, it must’ve been that other doctor who was here before you. He told me that she was dead. He must’ve lied to me,” and then went on explaining to her daughter why she can’t eat or drink any food we offer her because didn’t she know that there is a massive drought and famine going on in California and millions of people are dying?

The next thing you might think to do is to take the “If you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em.” approach and start telling the patient that you believe their delusional ideas. This is often born from a well-intentioned (but desperate) desire to form an alliance. Perhaps shortly after trying to present them with (what you thought was) bulletproof evidence of their delusions and failing miserably. Chances are that you’re either afraid that disagreeing with the patient about their delusions will make it impossible for you to form an alliance with them, or you think that by pretending to buy into their delusions they will think of you as on “their side” and let you start treating them.

Unfortunately, should you try this approach, you will find that this also doesn’t work. Even worse, it makes things harder for you in the long run. If their delusions are true, why do they need medication? Why aren’t you ordering an MRI if you agree that the CIA really has implanted no less than fifteen different tracking devices in the patient’s body? When/if they do take medications and their delusions start to soften, how are you going to explain to the patient about why you, uh, lied to their face repeatedly? This is perhaps the major problem with collusion. You can no longer represent yourself as a trustworthy individual that your patient can rely on to be honest.

A Happy Medium

With some guidance from my attendings, I eventually converged on an approach that consists of two strategies:

Validating the person’s feelings about their beliefs, without saying that you believe they are true.

“Yes, it must be terrifying to believe that every time you are out in public, there’s a group of people trying their best to murder you. I would be frightened too!”

Being candid with the patient about what you think: when asked directly, when explaining your diagnosis to the patient, and in other select situations without making the patient feel that you are constantly trying to belittle them.

“Since you’ve asked, Jim, I’ll be honest. No, I don’t think that your neighbor is spying on you using secret rituals taught to him by spirits of his Aztec ancestors.”

“Nancy, I know that we will probably see things differently, but as your doctor I have a responsibility to you to be honest about what I think is going on. I think that you have schizophrenia and that many of these worries that you have are part of your illness.”

“Ludwig, I know that you’re worried that your nurse is an expert killer-for-hire, but I’ve worked with him for 4 years now and I can promise that he will not harm you.”

Why this approach?

First, the obvious. We do not collude with a patient’s delusions because we do not want to reinforce the delusions. Your goal is to form a relationship with your patient where they can (1) trust that you have their best interests at heart (2) believe that you will honestly and reliably report your perception of reality to them. If you accomplish this — even a little bit — you will be one of the people that your patients will reference as a source of truth when they begin to question their delusional beliefs.

These two strategies also help maintain your integrity in the eyes of the patient — and in your own estimation — as an honest physician who has their best interests at heart. I find this works particularly well if you couch your honesty in language that conveys to them that you believe that it is your responsibility to tell them what you really think,1 while conveying to them that you understand they may not see things the same way.

You will probably be surprised at how well patients can tolerate this disagreement as long as your patient believes that you take how they feel seriously. Even patients with poor insight can understand just how outlandish their delusions seem to others. Most are so used to being disbelieved that they already assume they have to work to convince you of their claims.

Strong Convictions, Loosely Held

As someone who has a tendency towards the pragmatic, I want to emphasize that you should not underestimate the importance of feeling that you have maintained your own integrity in your dealings with your patients. I have come to believe that the alliance between you and your patient depends heavily (if not primarily) on your ability to be genuine with them. This requires you to feel as though you are acting in alignment with your own beliefs. If you don’t, your patients will likely notice that you are hiding something from them, and you will not be able to do anything to disabuse them of that (correct!) notion.

Your general rule should be that you do not collude, regardless of how significant or meaningful you think it would be to do so, because collusion erodes your ability to form an honest, genuine connection with your patient, which is the sine qua non of durable treatment.

Let Me Add Some Nuance

Are there times where its ok to just collude just a little bit? Assume the answer is “No” except in extreme circumstances. For me this is partially a self-discipline thing; I know I can be a bit impulsive and I want to avoid getting into the habit of reflexively colluding with things before I have really thought it over. More generally, I think it is extremely difficult for us to know what a patient will (or will not) perceive as a major or minor endorsement of their delusions. There are always extreme cases where pragmatism trumps everything for the sake of patient or staff safety. If the patient has you cornered in a room and is threatening to beat the shit out of you unless you promise to order an x-ray of their wrist so they can finally prove that NASA implanted them with a microchip, collude away!

Not colluding with your patient’s delusions is not the same thing as constantly going out of your way to challenge their delusions. Do you have that friend/relative/sibling who always wants to argue about everything you disagree with them about all the time? Do you enjoy spending time with that person? Do you have positive feelings about them? Do you see them as someone who you can be honest with about intensely personal topics without fear of reproach or argumentation?

It is OK to express your genuine uncertainty about things that are plausibly not delusions. There are, in fact, organized groups of violent criminals that sometimes work to kill a single individual who has gotten on their bad side. Maybe you’ve heard of gangs before? It is not unreasonable to think that if a patient is from an area with lots of gang violence and are the sort of psychotic who e.g. screams in people’s faces, they might very well have rubbed the wrong person the wrong way.

Finally, this approach assumes that the patient in question has the ability to actually get better in some meaningful way. I concede that there is a subset of patients who are so chronically and floridly psychotic that some of the ideas behind this approach sort of fall apart. The problem is that it’s pretty much impossible to know who those patients are ahead of time, unless you have a phenomenally detailed history of treatment that you believe is totally reliable (you almost never will).

Don’t Just Do What I Say

If I have persuaded you of the virtues of my approach, you might be tempted to adopt my reasoning wholesale without considering the implications of doing so. No approach is universally applicable and to understand when and where exceptions are (and are not!) appropriate you need to do more than just ape me. Let me show you what I mean:

In my residency there was a clinical interviewing class. One of the residents would interview a patient from our inpatient unit, someone they had never met before, in front of the PGY-1 and PGY-2 classes, plus an attending. After the interview, we would discuss the patient and give the interviewing resident feedback about various aspects of their interview.

One week, our patient was a young woman in her early 20s who we’ll call Emily.2 Emily was clearly, indisputably schizophrenic. She had auditory hallucinations, a bizarre affect, and a very complex system of delusions. One of these delusions was that she was actually a male. She said that she knew this was the case because, when she was born, (((someone))) swapped her soul into a woman’s body. This, incidentally, is also why she “knew” that her parents weren’t her actual parents. She also said that her real name wasn’t actually Emily, but another (distinctly male) name, and wanted to be referred to by male pronouns. Somewhere along the way, someone decided that this meant that Emily must have a primary diagnosis of gender dysphoria; she had even been started on testosterone!

After the interview when we all started discussing the case, I used female pronouns to refer to Emily, and referred to her by her birth name. I chose to do so because Emily was clearly psychotic and her belief that she was actually a boy trapped in a woman’s body was very clearly the product of her psychotic delusions. At the time, I wondered if this would upset anyone, but nobody said anything to me directly. I later learned that this had upset quite a few people and, I suspect, led them to believe that I disliked trans people and was being intentionally disrespectful to Emily.

I had a similar experience earlier this year when I admitted another young woman who I will call Leah3 while I was moonlighting. Leah was also very clearly psychotic, maybe a touch manic, and had many cluster B traits. She told me that she was a man. In fact, she was a very specific man named Yeshua, who I might be familiar with as Jesus, who she very earnestly said that she was the literal reincarnation of. She seemed pretty clearly delusional to me. A couple weeks later when I returned for another moonlighting shift at that hospital, I inquired with one of the psychiatrists about how Leah was doing. “Oh, Leah? The one that’s trans only when she’s psychotic? Yeah, she got better with antipsychotics and we discharged her.”

I found it kinda odd that this psychiatrist talked about Leah as being trans only when she is psychotic. She’s not trans, she’s just delusional! Maybe I am reading too much into this, and “trans” has become shorthand for “any person that feels that they are the opposite gender for any reason.” Maybe that was just the most salient feature about this patient that he recalled. Still, I think it says something that this psychiatrist didn’t say “Oh yeah, that girl who said she was Jesus.” It felt like he was colluding with the delusion, just like some of my co-residents did with Emily.

Where this position came from isn’t much of a mystery. The debate around proper treatment of gender dysphoria and transgender individuals has become heavily politicized. Academia is home to some of the most extreme left-wing opinions (medical academics being no exception4). And so the maximally left-wing position of believe anyone who says that they are trans for any reason (and don’t you dare question them because only transphobes do that) thus infects itself into medical education and people reflexively start applying it even in situations where more careful consideration is needed.

Let me say, very clearly, that I think that trans individuals deserve to be treated with no less dignity and respect than anyone else. My personal default is to address people by the names and pronouns that they prefer, even in (the pretty rare) cases where I privately hold reservations about the sincerity of a claimed identity;5 this is mostly because I try to be very charitable, am rather conflict averse, and am still a bit afraid of being blackballed for saying the wrong thing.

But just because this is my default does not mean that it is the best way to help my patients. This is precisely why it is important to be able to articulate your approach and feel confident that you have chosen it because it benefits your patients. Without these two things you will find yourself simply doing either what you find comfortable or what you think others expect you to do.

Oh, and lest you think I am only talking to those of you who have a positive view of trans individuals, let me address those who are reading and are generally inclined to reject trans identities. You, too, need to be able to articulate your rationale for doing so and be convinced that your approach is the best way you know how to help your patients.

Is This A Special Case, Though?

If I have done my job thus far it should be no mystery to you at this point in the essay why my default is not to take claims of gender dysphoria/transgenderism at face value in a psychotic patient. As I mentioned, it is always reasonable to ask whether something presents an exception to the rule; rigidity is not a virtue. That said, I do not think that gender dysphoria represents a special case that permits a general exception to the rule of non-collusion for many reasons. Let me address a few.

Parsimony

You might be thinking that I was being too hasty in my assessment of Emily and Leah. Surely, you might object, people can have both gender dysphoria and schizophrenia! And, yeah, I agree, that could happen; certainly I would have no issue with using a patient’s chosen name and pronouns if I knew that they consistently expressed a trans identity with a non-delusional foundation.

However, I had no information suggesting that this was true for Emily or Leah, and reflexively assuming an independent diagnosis of gender dysphoria violates my general rule of starting with a parsimonious approach for initial diagnoses. I find diagnostic parsimony to be valuable for many reasons, but that’s for another essay. Here, briefly, it helps me avoid introducing conflicting treatment goals and avoid overtreatment.

Invalidation Is Part Of The Job

Might patients feel invalidated if we do not use their preferred name and pronouns? I mean, sure, but let’s think about a less politically charged example.

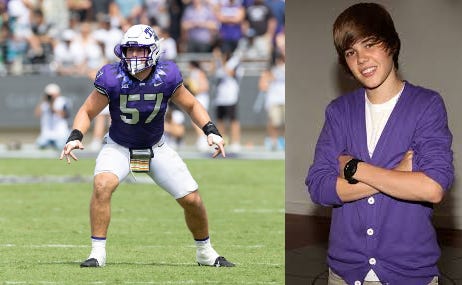

I once had a manic patient who told me he was Justin Bieber (this was very funny because he was like 6’4” and built like a linebacker. Justin Bieber is 5’9”). He really, truly believed he was Justin Bieber. He insisted I call him Justin and signed all of his legal documents “Justin Bieber.” When I asked him why he didn’t look anything like Justin Bieber, he gave me a withering look and said that I must not be familiar with how camera lenses work.

I did not call him Justin and — despite the fact that he really did seem to believe that he was Canadian heart-throb Justin Bieber and really did get upset when I called him by his real name — exactly zero people had problems with that.

“Ok sure,” you say, “but there was literally no chance that this guy was Justin Bieber, and there is a chance that a psychotic patient could have true gender dysphoria.” Ok, fine, but nobody actually thinks about delusions that way. We readily assume a delusional worldview behind things that are far more common than gender dysphoria all the damn time. The incidence of gender dysphoria in adults is probably somewhere around 0.75%. The CDC’s 2016/2017 report on stalking found that 31% of women and 16% of men reported being stalked at least once in their life. When an obviously psychotic patient tells you that they are being stalked, are you going “huh, well, there’s a 30% chance that’s actually true. I should take them at their word and treat this as true until proven otherwise?” Of course not!

We also do other extremely invalidating things to our psychotic patients on a routine basis. Consider how invalidating it must feel for a patient to simply be told their diagnosis! What must it be like to hear the equivalent of “Oh, the mortal terror that you feel on a daily basis, that you know to be real and true? Yeah… we definitely don’t believe that, and almost certainly aren’t going to investigate it. By the way, if we think you’re really causing problems? Well, we’ll force you to undergo treatment involuntarily.” This is to say nothing about invalidating involuntary treatment is.

For My Friends With High Trait Agreeableness

Finally — and this is a broader philosophical point about our work — we will inevitably do real harm our patients if we treat certain topics as “off limits” for questioning and start relying on social or political dogma to guide our treatment. Just as we should not collude with our patients in their delusions, we should not collude with our own fears and desires to ignore the world as it actually is and pretend that it is as we want it to be.

We must also recognize that collusion with these simplistic fantasies is (1) part of the human condition and (2) often smuggled into our behavior under the pretense of doing “good.” It is not hard for me to sympathize (on some level) with those who would like the answer to “How do we determine if a person genuinely has gender dysphoria?” to be “We only need to take people at their word, no matter what, because that is the kind thing to do, and the kind thing is right and good.”

Anyone who has done therapy-based work will know the intense discomfort that comes with questioning the truth of a patient’s narrative about certain socially and politically sensitive topics. How does one explore the possibility that a patient who has been the victim of a number of physically abusive partners might be provoking and enabling their abusers? That a patient might have adopted a particular sexual orientation as an act of avoidance? That a patient seems to be exaggerating their trauma in order to avoid change or garner sympathy?

I believe there is a deep desire to avoid asking these sorts of questions that extends beyond our desire to simply avoid the discomfort of social faux pas. To learn the answers to these questions might complicate the straightforward narratives we construct for ourselves to justify our own behaviors, thoughts, and beliefs. These complications, in turn, require us to reckon with the harm we may have caused our patients by refusing to acknowledge the nuance that was there the whole time.

This is very hard thing to admit to ourselves! Understandably so, because the next question waiting right around the corner is “What other well-intentioned but harmful things might I be doing? And how do I know what they are?!”

Awareness of this uncertainty, alas, is the psychiatrist’s lot in life. The only antidote to uncertainty that I have found is to be confident that you are trying to do your best and working to learn how to do even better. Not to do your default. Not to do what makes you comfortable. Not to do what you think others want you do to.

Because, you know, it is

Not her real name

Not her real name

For those of you who don’t believe me, I have many, many stories from my time at Penn State. Here’s one. Once, at a mandatory lecture on race in medicine, the head of our DEI office who was a JD (i.e. no medical training, and didn’t even pass the bar to boot) told us that it was racist for us to have a higher index of suspicion for sickle cell disease in black patients. Oh, also that it was quite problematic to consider using different antihypertensives for black patients.

I can think of a couple cases of patients in their early teens who seemed to adopt a trans identity when it suited them and dropped it when it didn’t, as well as at least one adult who seemed to have adopted the identity in an attempt to find something to blame for their unhappiness in life.

I've been thinking a lot this last year about how to approach someone with paranoid delusions, as unfortunately I had a delusional friend. I don't have any medical authority over my friend, but I took a similar line. I quickly realised direct confrontation of facts wouldn't work, so I tried to take an agree-to-disagree type approach. In the end I expressed too much doubt about some thing (whether some public figure had really been assassinated) and when my friend went stopped taking antipsychotics and the delusions worsened, my name got plastered on social media as a secret agent engaged in spying.

I'm not really sure there was a way to avoid that and also still be friends. Obviously the approach most people take is to consign people like this to institutional oblivion, but everyone needs a friend.

This post was quite emotionally difficult for me to read and process. I don't mean that as an indictment. I read it when you originally posted it, and came back today to see if it landed differently, or if I could work out for myself why it had such a strong effect. It hit softer on the second read, but wasn't much different in quality. I've come to identify two initial registers of feeling and two initial conclusions about this experience.

First, the aspects your post that related to questioning patients' trans identity felt alarming to me in relation to my experiences as a trans person who has gone through and received treatment for a temporary period of psychosis (in which the stress of gender dysphoria and denying my own trans identity to myself seems to have been a significant factor). "Trans=delusional" is already such a common and damaging stereotype, and it's even nastier to deal with if you've actually had or have delusions. While I really, really hope that psychiatric professionals are in fact able to ethically discern gender from gender-related delusions in a way that makes them worthy of their patients' trust, I also can't ignore how quick members of the general public are to use their equivocation of transness and delusion to try to put you in your place. Choosing to believe that a given medical professional won't do the same (which I want to do, in at least some situations)--in order to do that, I have to actively suppress strong and experientially well-founded instincts for the preservation of my safety and dignity. I know not everybody in our demographics will have the same experiences or instincts. More that I feel taken aback by just how brightly those alarm lights started flashing when I got to those parts of your post.

Second, you post felt quite uncanny to me for another reason: the strategies you recommend for interacting with delusional patients are pretty much a carbon copy of the ones I've worked out on my own, as a trans person, for dealing with the wide range of precious misconceptions that cis people entertain about trans people (I won't even call them prejudices because half the time, it ain't even "pre" the "judice", it's just bad "judice", eyes wide open.) But, yeah. Reflexive collusion with those precious misconceptions will only make things worse for you and others down the road. Collaborate only when you are under threat and only to the extent necessary to de-escalate to an acceptable risk level. Validate their feelings as feelings, not as facts (and don't expect them to consider your feelings). If engaging seems beneficial, redirect their attention to the factual exigencies of the situation with a factually grounded and confidently delivered explanation, and don't pretend to have answers you don't. Pick your battles, know your own tendencies and energy and when not to engage at all.

Funny stuff, huh.