Wot's Uh... The Deal With: Auvelity?

Is the DXM-bupropion combo really faster at treating depression than everything else?

Back in August of 2022 the FDA granted marketing approval to Auvelity, a combination of dextromethorphan and bupropion (DXM-bupropion) for the treatment of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD). Axsome, the company that developed it, hyped it up as:

The First and Only Oral NMDA Receptor Antagonist for the Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder in Adults

and that Auvelity:

represents a milestone in depression treatment based on its novel oral NMDA antagonist mechanism, its rapid antidepressant efficacy demonstrated in controlled trials, and a relatively favorable safety profile.

Obviously this is standard marking talk — ketamine would like to have a word about that “first and only oral NMDA receptor antagonist” thing — but let’s give credit where it’s due. Outside of ketamine, which is not easily accessible, DXM-bupropion offers a mechanism of action that is separate from the SRIs/SNRIs and the atypical antidepressants. This is a good idea and is exactly the sort of thing that we want drug companies to be doing instead of just making another copycat drug.

Unfortunately, I never learned much about it. Back in 2022 I was a freshly minted PGY-2; I wasn’t exactly keeping on top of the latest developments, what with all the learning how to do the basics of psychiatry. With the recent hype around ketamine and interest in NMDA receptor based mechanisms, now seemed as good a time as any for me to give it a closer look.

Some Neurobiology

My favorite part about writing this article is that I get to tell you about the NMDA receptor because it is Just. So. Cool.

Imagine that you are one of God’s post-docs in brain R&D. At the moment, you’ve got the basics down: action potentials are zipping along axons (you just solved that one with insulation and saltatory conduction), neurotransmitters are being dumped into the synapses and binding to their post-synaptic receptors, kicking off another action potential, and so on. With all the basics in place, you need to start adding the mechanisms necessary for the brain to organize and adjust its own networks — God keeps talking about how he wants to do some weird QA test with a snake and an apple and needs whatever thing this brain is going in to be able to make “independent moral judgements” and who are you to question the Divine? Specifically, you want your neurons to be able to adjust the strength of their connections to one another (i.e. to adjust the “weights” of their signals).

You heard about this concept called Hebbian Learning, where “neurons that fire together, wire together.” Sounds like a decent place to start; after all, neurons that are firing action potentials around the same time as one another are probably responding to related stimuli. Practically, this means you need to design a coincidence detector, some mechanism that can detect that the pre-synaptic neuron and post-synaptic neuron have fired, in that order, without too much of a temporal gap between those two events. You also need to make sure that there is some way to indicate a causal link; your post-synaptic neuron might be on the receiving end of signals from dozens of different neurons and you don’t just want to strengthen them all indiscriminately.

Oh by the way, the Man Upstairs just told you that the goal is to do this as simply as possible. Apparently there’s some sort of issue with the NIH grants going on?

This is a tough problem. Designing new neurons to monitor the neurons you already have would take too many resources — why God spent so much money developing all of those types of glial cells will never make sense to you — so coincidence detection needs to be something that the post-synaptic neuron can do on its own. Membrane proteins are pretty low in terms of overhead (at least relative to a whole new cell), so you decide that’s the best place to work from.

What is the most obvious signal that an excitatory presynaptic neuron has fired? Glutamate binding to a post-synaptic receptor, obviously.

This is an easy enough place to start. You’ve already designed a slew of receptors that bind glutamate, so you whip up a protein real quick. At its core, it’s a ligand-gated calcium channel. You chose calcium because it’s readily available and works as a second-messenger all by itself; you’re going to need something to kick off the protein synthesis required to modify your synapses.

This new receptor also features two binding sites in the synaptic cleft. One is for glutamate, obviously. The second you got a little fancy with, this one requires glycine.1 Why? It’s a regulator. See, normally there’s plenty of ambient glycine floating around in the synaptic cleft to bind this site, but its concentration can be adjusted by the local astrocytes. So, if you’re worried about excitotoxicity or just want a way to fine-tune response, you can have astrocytes2 suck up some extra glycine and viola, you’ve effectively inactivated some chunk of your NMDARs.

OK, so we’ve got one half of this puzzle. What indicates to a post-synaptic neuron that it has fired? A change in voltage across its the membrane.

It’s… not actually a very hard puzzle, tbh.

This is also nothing other proteins haven’t done before. You could just add in one of those plugs that the other voltage-gated channels use, but that’s not going to impress the literal creator of the universe, so let’s be clever instead. What if we could use the ions themselves? Turns out that if you design the ion channel just right, Mg2+ and Zn2+ ions will wedge themselves into the channel and block it off, but will pop right out when the membrane is depolarized.

Now you have your coincidence detector. A single receptor that will only open when:

(1) The pre-synaptic neuron fires, releasing glutamate to bind the NMDAR

(2) The post-synaptic neuron depolarizes and kicks out the Mg2+ ions from the NMDAR’s channel

(3) Those two things happen close enough together in time that the glutamate concentration hasn’t diminished and the Mg2+ ions haven’t found their way back to the channel.

Then, when these two events align, the calcium flowing into the cell kicks off a cascade of different pathways that strengthens the connection between the two cells (i.e. long-term potentiation.) In fact, you can even use the NMDAR to weaken synaptic connections (long-term depression3) by tuning the connection-weakening pathways to respond to low levels of calcium influx; something that might occur if the NMDARs are only being weakly opened.

Was this important for you to know for the purposes of this article? Absolutely not, but — and I cannot emphasize this enough — it’s so cool, and if you don’t think so you need to go searching for your sense of wonder.

Some Psychopharm

The inclusion of bupropion in Auvelity is something of a fakeout. It’s allegedly there to act as a CYP2D6 inhibitor and nothing else, but, c’mon Axsome. It’s not like there aren’t a bunch of other non-psychoactive 2D6 inhibitors out there. Nuedexta uses quinidine.

Anyway, the 2D6 inhibition is both to increase DXM’s quite short half-life of ~3 hours, but also to increase the half-life of its active metabolite dextrorphan (DXO). As with most psychiatric drugs, DXM and DXO do not have a single, obvious mechanism of action, despite what Axsome would like you to believe.

DXM has relatively high affinity for SERT, NET and the σ1 receptor.4 DXO is quite a bit weaker than DXM at SERT and NET, but its affinity for the NMDA-R is ~4x higher than DXM’s and slightly higher at σ1. There is also a third mystery major metabolite via 3A4, (+)-3-methoxymorphinan and (of course) nobody actually knows what that thing does or if it’s important, so let’s just not talk about it too much.

I point this out just so you don’t let the marketing folks pull the wool over your eyes too hard by talking about “The First and Only Oral NMDA Receptor Antagonist for the Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder in Adults!” Sure it is, if you conveniently ignore that DXM just happens to be an SNRI.

In a past life, I would’ve spilled a lot more digital ink talking about mechanisms and binding affinity… but I just don’t think it’s worth the time anymore. When it comes to clinical psychopharm, mechanisms are nice and all, but all that really matters are the clinical results, so let’s talk about those.

The Clinical Results

There are two major clinical trials worth examining. A phase II trial published in the July 2022 issue of AJP, and a phase III trial named GEMINI published in the May issue of the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

The Phase 2 Trial

This trial (NCT03595579, no fun acronyms here) was a double-blind RCT with bupropion as an active control. Patients were randomized to receive either DXM-bupropion 45/105mg BID, or bupropion 105mg BID. A total of 97 individuals were enrolled, but only 80 were included in the efficacy analysis; 17 were excluded by an independent reviewer (more on this below). Primary endpoint was overall treatment effect on the MADRS5 at weeks 1-6 of treatment. Just as a reminder, the MADRS is a 10-item scale with a maximum score of 60. A reduction of 8-9 points on the MADRS corresponds to a single step down on the GCI-S6 (Leucht et al. 2017).

First, I’m glad to see them use bupropion as an active control here; when one of the two components of your drug has known efficacy at the dose prescribed in treating the exact thing that your new combination medication is treating I think you should be required to have an active control arm (maybe you are?). The dose of bupropion is about 30% lower than the typical average dose of around 300mg, but bupropion has efficacy at 150mg.

Second, they used an independent assessor who was blinded to treatment assignment. This assessor’s job was to review patient charts and ensure that they met study criteria, and would exclude them from the efficacy analysis if they did not. Usually, I see patient eligibility handled by having multiple reviewers who evaluate the patient themselves and then hash out disagreements between one another. This process is obviously subject to a bunch of interpersonal dynamics that will inject bias into the decision making, so it’s nice to see them try and solve for that. It seems like this was a useful approach; the independent reviewer excluded a total of 16 patients (a full 16% of the original group!) who did not at least meet criteria for moderate MDD.

The most interesting part of the study design is how they approached blinding. They did the typical things double-blinded studies do: using identical looking pills, not telling the participants or the clinical staff which patients got what, etc. They also blinded the investigators at the clinical sites to the purpose of the study and the primary outcome measures(!). Investigators were:

…provided a blinded protocol that presented the trial as a safety study with exploratory efficacy assessments. Detailed discussion of the efficacy analysis was limited to the statistical analysis plan, which was not provided to the sites.

Makes sense on paper; I’d be curious to know if it actually reduces observer bias in practice.

Demographics

Patients needed to have a MADRS ≥ 25 and a CGI-S score ≥ 4. They could have previously been on an antidepressant, but had to wash out for 7 days or 5 half-lives, whichever was longer (max washout period was 4 weeks).

The following (pretty typical) exclusion criteria applied:

No failure of ≥2 antidepressants during the current episode.

No comorbid:

OCD

Panic disorder

Bipolar disorder

Any history of psychosis

SUD within the past year

Hx seizure disorder

One wonders just how many patients were previously on medication, and if any of them happened to already be on bupropion, but that information was not included in the paper.

Otherwise, the demographics look pretty unremarkable. I continue to think that score ranges should be reported when there is a scoring floor for study entry, particularly when the statistics provided do not let you determine those ranges on your own. Going just 2 s.d. south of the mean MADRS for the DXM-bupropion group would put us at 23.8, below the cutoff for study entry!

Outcomes

Of the participants in the efficacy population:

34 (79.1%) completed the trial in the DXM-bupropion group

26 (70.3%) completed the trial in the bupropion group

Treatment adherence was quite good based on tablet counts (>90% for both groups), which was further confirmed by the fact that 93.1% of participants had measurable bupropion concentrations at the end of the study. This is great confirmation, why don’t more studies do this?7

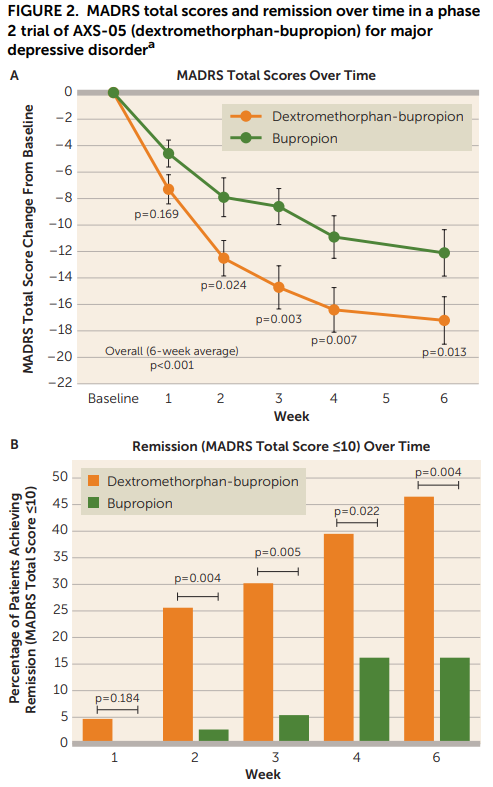

Looking at Figure 2, the results look pretty good for the DXM-bupropion combo:

…but maybe a little too good? Like, what’s up with the bupropion-only group and its paltry 15% remission rate at week 6? A <15% response at week 6 is even worse than placebo in meta analyses of antidepressants! This meta analysis of 7 RCTs shows that bupropion alone typically has remission rates of about 40% at the 6-8 week mark. Even if that is a little too high, and we say it’s more likely to be 30% a la the rest of the SRIs/SNRIs, this active control group is quite unusual. It could be that the independent auditor actually did a good job and removed the mild cases that were more likely to spontaneously remit. Maybe their neat blinding idea eliminated a large proportion of the placebo response? Is 210mg is not a sufficient dose for the majority of individuals here? Something odd is going on.

That said, even if the study population is a little strange in other ways, this data obviously provides strong evidence that DXM is doing something more than just bupropion alone. The DXM-bupropion combo also kicks in faster, which of course is the theoretical selling-point for this drug - more on that later.

Looking at the numerical outcomes in Table 2, things continue to look decent for DXM-bupropion:

I will note that the primary endpoint here is a weird one to me: “average of change from baseline for weeks 1–6” and seems very much like one of those endpoints that you choose because you know it’s going to inflate your numbers. I’m ignoring that and just looking at the Week 6 results here, though I’m open to someone who can explain to me why I shouldn’t.

Still though. Small study, wide confidence intervals. Certainly should make you update in favor of DXM-bupropion having efficacy in MDD, but not a slam-dunk.

GEMINI

The GEMINI trial was a pretty conventional phase double-blind, placebo controlled RCT than ran for 6 weeks. DXM-bupropion dosing was the same 45-105mg qDay for 3 days, then 45-105mg BID, just like in the phase 2 trial.

Inclusion criteria was pretty standard as well: At least 4 weeks of MDD based on the Structured Clinical Interview, a MADRS ≥25, and a CGI-S ≥4.8

Exclusion criteria was the same as in the phase 2 trial: no other major psychiatric comorbidities, no treatment resistant depression.

Demographically, again, nothing too special. This time, they reported ranges for the MADRS and CGI-S. Good job.

Efficacy analysis was a modified intent-to-treat which included all patients who were randomized, received at least one dose, and had at least 1 post-baseline efficacy assessment. Primary endpoint was change from baseline in the MADRS at week 6. Secondary endpoints were examined in a pre-specified fixed-sequence (i.e. they would only be reported if the previous endpoint in the list was statistically significant.).

Outcomes

Let’s begin with the beginning: how did the primary outcome fair?

While the p-value suggests that we can be pretty confident in DXM-bupropion’s superiority vs. placebo, a ~4 point improvement is nothing special. The average antidepressant shows a 3-point improvement, and a 4-point improvement on the MADRS is about half a point on the CGI-S.

It also seems like the strength of the placebo response is a bit higher than is typical? I am not sure if antidepressants have been subject to the same placebo inflation that the antipsychotics have, but if they are I bet Stefan Leucht has already written a paper on it. Ok, he’s not first author, but of course he was a co-author, and it turns out that placebo response rates (~35%) have not really changed since 1991.

In terms of remission (MADRS ≤ 10) and clinical response (reduction of ≥50% from baseline MADRS), I also don’t think there’s that much here to be excited about:

Again, yes, a statistically robust separation from placebo at week 6 for both response and remission, but still nothing that we haven’t seen before from individual studies of other antidepressants. Sure, a response rate of 54% at 6 weeks is higher than average, as is a remission rate of 40%, but many other antidepressants have posted similar results in the early days only to come out looking pretty average once the meta analyses get done.

Overall, in terms of outcomes, the DXM-bupropion combo doesn’t seem to me like it offers any major improvements over existing antidepressants. Which, you know, shouldn’t really surprise anyone at this point. Throw it on the shelf, add it into the rotation when the patent expires in, let’s see… November 2034, right?

Well, maybe, but the big marketing emphasis for Auvelity has been to say “Ok, ok, it might not be more effective, but it acts faster than those other antidepressants that don’t show results until weeks 6-8.” And, if you look at Figure 2 from this study, you can see why they might want to make that argument:

The problem for Auvelity’s marketing is that this relies on a misapprehension about the speed at which other antidepressants work, specifically, the commonly repeated myth that antidepressants “don’t work” until 6-8 weeks of treatment. I mentioned in a previous essay that data from papers like Uher et al. do not bear this out, and that a substantial proportion of patients on antidepressants will show a marked response or even complete remission within the first 3 weeks of treatment.

However, that paper did not provide information as to how clinical symptoms improve during the course of those 3 weeks. I would agree that it would be a meaningful difference if the DXM-bupropion combo showed significant improvements 1-2 weeks faster than the other antidepressants. But does it?

Fortunately, Posternak and Zimmerman, 2005 has the data we need to try and answer this question. They analyzed 47 double-blind RCTs of antidepressants that reported weekly changes in the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD) to see what the typical trajectory in scores was over the course of 6-weeks.

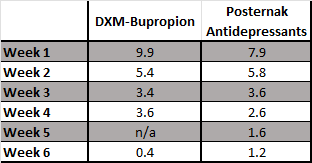

While the HAM-D and the MADRS are different measurement instruments, they correlate quite closely with one another, so I think it is reasonable to assume that the percentage change here at each week will be comparable. Let’s see how the results from the GEMINI study stack up when you put them side-by-side:

OK, so, DXM-bupropion in the GEMINI study did frontload an extra 10% of its total benefit (an extra ~1.6 points) at week 1. Put another way, DXM-bupropion delivered 67% of its total benefit at 2 weeks, while the pooled treatment groups in the Posternak paper “only” delivered 60%.

Is that a clinically meaningful difference?

For the average patient, I think you’d be pretty hard pressed to say it is. Even if we assumed that a 1.6 point gain was entirely concentrated in the single worst aspect of their depression. Also remember that you need an ~8.5 point change for a full step down on the CGI-S scale.

But, let’s not just think about the average patient, let’s think about the more severe cases. How about the individual(s) with the highest baseline score on the MADRS at study entry: 48. Let’s assume that effect size does not vary with baseline severity (it’s not clear if it does or not), and that these very sick individuals got the same 47% decrease in their MADRS (on average) that individuals with baseline scores right on the mean. That would translate to an average decrease of 22.7 points, 9.9 of which would occur in the first week of treatment. Again, lets see how this compares with the Posternak data:

OK, so now we get 2 points more at week 1 instead of just 1.6 - a whole 0.4 more! At 4 weeks, DXM-bupropion will theoretically have improved the MADRS by 22.3 points vs. 19.9 points with a generic antidepressant. A difference of 2.4 points. Again, is this a clinically meaningful difference? And, again, maybe if DMX-bupropion reliably improved the single worst aspect of a patient’s depression by two points, and that patient was really, really depressed.

Longer Term Data?

Unfortunately, there doesn’t seem to be much in the terms of longitudinal data beyond two posters from open-label trials. The first reported a remission rate of 69% and a response rate of 83% at 12 months. The second reported a remission rate of 68% and a response rate of 86%, also at 12 months. These numbers are really nothing special relative to other antidepressants and probably not even relative to placebo. Remember that even in moderate untreated depression about 75% of patients will experience complete remission at 12 months.

What about Anxiety?

Whether or not bupropion is relatively contraindicated in patients with significant anxious symptoms is an evergreen topic in psychiatry (spoiler: it’s not), and Axsome happened to present poster data on anxiety outcomes as well, so I’ll briefly summarize.

This data comes from one of the open-label trials I mentioned just above called EVOLVE. It enrolled 186 patients who met the same criteria required for entry into the RCTs, plus they needed to have trialed at least one antidepressant during their current depressive episode. The study collected HAM-A9 scores at baseline and at various points throughout the study. Here’s their table for remission (defined as a HAM-A ≤ 7):

I couldn’t actually find any good meta-analyses that gave good numbers for comparison, but I did find a decently sized (n = 566) paroxetine RCT in patients with GAD that had a remission rate of 36% at 6-weeks.

Does that mean there’s something here? Eh, I think all you can conclude from this is that DXM-bupropion does improve anxiety — certainly doesn’t seem to make it worse — but you can’t really draw any conclusions about superiority given that this was open-label, without any sort of control group for comparison.

I’m Not Impressed

So, look, there are two fundamental questions here that we have to answer: (1) how much suffering would the average patient avoid by dropping their MADRS score by 1.6 points ~2-5 weeks earlier than with other medications? (2) Is avoiding that suffering worth spending approximately $47.10 a day (the current cost of two tablets of Auvelity, per UpToDate)?

I think the answers are: (1) probably not much, and (2) probably not worth $47.10/day.

First, like literally every other antidepressant that has ever been developed, the new shiny drugs put up great results in early trials and then regress to the mean and look like every other antidepressant after a couple of decades. I see no reason to believe that the same exact thing won’t happen to Auvelity.

Second, the average patient we’re seeing in the clinic with “depression” is usually on the more mild/moderate end of the spectrum, so the real improvement in the first week or so relative to another antidepressant will probably be undetectable to yourself and the patient.

Assuming that the improvements are concentrated in the single worst depressive symptoms, there could be a case for using Auvelity in very depressed individuals.

…there could be a case, but there isn’t, because even then you should probably just DIY it by prescribing bupropion and DXM separately. Prescribe bupropion SR 100mg BID + whatever formulation of DXM you want (there are plenty of tablets and liquids available). Even if insurance won’t cover it because they think you’re being too clever and want to save them too much money, DXM is dirt-cheap out of pocket (45mg in tablets would cost ~50c/day, or 90c/day for the cheapest liquid formulation I can find).

The bottom line is that I don’t see anything particularly special about the DXM-bupropion combination relative to other antidepressants. Maybe there will be some data to suggest differential effectiveness in certain subpopulations, but until then, I’ll be DIY’ing this or waiting until 2034.

I know there are allosteric sites but you are a hypothetical grad student on a tight budget so let’s just assume that those are happy accidents that you bumbled your way into.

Different PhD in your lab did those, no idea how they work.

Not to be confused with dysthymia or persistent depressive disorder

The sigma receptors were previously classified as opioid receptors, but it turns out they are a totally unrelated receptor family.

Montgomery-Åsberg Depression rating scale.

Clinical Global Impressions - Severity scale

It’s expensive, probably

Clinician Global Impression - Severity - A 4 means “Moderate Illness”

Hamilton Rating Scale - Anxiety

High quality note. Thank you.

Great article, about a medication I’ve never come across in practice! Did it not impress you

that it was superior to another antidepressant, rather than just placebo as in most drug trials?